Posted on February 7, 2014

by Ian A. Mance, SCSJ attorney

On November 2, 2013, I was involved in a serious car accident that I was lucky to walk away from. The force from the collision was at once frightening and disorienting. In the minutes that followed, concerned motorists and pedestrians ran to my vehicle and checked on my well being. They called for police and an ambulance, both of which were quick to respond and offer medical attention and help securing the accident scene. I made it home that night, shaken but in one piece, thanks in part to the kindness and quick action shown by the first responders who came to my aid.

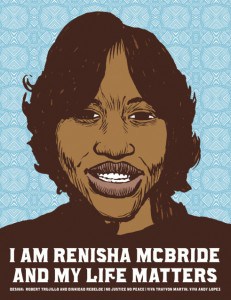

That very same night, Renisha McBride, a 19-year old woman from Michigan, was also in a car accident. Ms. McBride lived in Detroit, a city where budgetary cutbacks have resulted in 911 response times as long as 4 hours. Injured and dazed from the collision, and with no one around to call for assistance, McBride stumbled from her vehicle and made her way down the road into Dearborn Heights, where she knocked on the door of 54-year old Theodore Wafer, seeking help. Moments later, Ms. McBride lay dead on Wafer’s porch, killed by a shotgun blast to the face. Wafer, who is white, would later tell police he believed the 19-year old woman to be a threat and worried she might be trying to burglarize his home. He never opened his door.

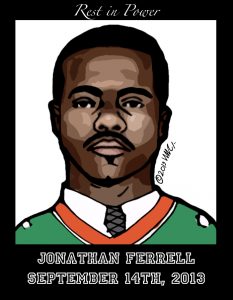

In the weeks following my accident, I thought often of Renisha McBride—and of Jonathan Ferrell, the Florida A&M graduate who had been in a car accident himself a few months earlier, just a two hour drive from me down Interstate 85 in Charlotte, NC. I am a white man, with all the privilege that entails. Both Mr. Ferrell and Ms. McBride were black. Like Ms. McBride, Mr. Ferrell had stumbled from his wrecked vehicle to seek help from the nearest home he could find. Charlotte police officer Randall Kerrick answered the homeowner’s call for help and, along with a number of other officers, arrived on the scene shortly thereafter. Encountering the disoriented Ferrell, Officer Kerrick took him to be a burglar, pulled his sidearm and fired 12 shots, striking him 10 times. Mr. Ferrell died on the scene, felled by the very officer from whom he’d sought assistance. Kerrick, like Wafer, would later tell his fellow officers that he perceived Ferrell to be a threat. None of the other officers had so much as unholstered their weapons.

Jonathan Ferrell and Renisha McBride’s deaths would go on to make national headlines. Their names quickly assumed a place alongside young Trayvon Martin—who would have turned 19 this week—as the newest faces of racial profiling in America and reminders of the dangers of implicit bias. As Wafer and Kerrick made their first court appearances, commentators from all quarters voiced their anger that accident victims, people who had done nothing more than seek help, could be met with—and lose their lives to—such senseless violence.

Even as an attorney who works regularly on issues of racial profiling and police misconduct, I too initially found myself amazed at the circumstances in which Ms. McBride and Mr. Ferrell lost their lives. I wanted badly to believe that the reason they had assumed such a prominent role in our collective consciousness was that their deaths represented a truly unique tragedy. We are all familiar with the phenomenon of “Driving While Black” (DWB), but Being an Accident Victim While Black? Is that a thing?

Statistical evidence, available in North Carolina under our first-of-its-kind data collection statute, makes one thing very clear: Police, statewide, treat black motorists with much greater suspicion than their white counterparts. What may surprise people to learn, however, is that this deeply imbued sense of suspicion does not necessarily dissipate when someone encounters police in the context of an accident. Just last month, I assisted an African-American family in North Carolina in filing an excessive force complaint against a pair of officers who physically attacked them following a car crash in which the family was involved. Frustrated that one of the women, emotionally distraught and bleeding from her chest, wouldn’t “calm down” to his liking, one of the officers—off-duty at the time—tackled her to the ground and broke her arm, resulting in her hospitalization.

A few weeks before, I’d met with a young black man, about the same age as I am, who was arrested by a local police department after calling to report his involvement in a car accident. Upon arriving on the scene, the responding officer ran his license and discovered the man had previously done a short stint in the county jail. The officer initially suspected DWI, but the man’s 0.0 Breathalyzer results quickly eliminated that possibility. Not knowing what to attribute the accident to, and apparently assuming that as the only black man on the scene he must somehow bear responsibility, the officer took him into custody. While records show he was arrested, no record exists to suggest that he ever faced any charges. For a time, he found himself, in effect, a ghost in the machine—suddenly in custody after calling police for help, a difficult night suddenly transformed into a nightmare.

The experience left him feeling like there was literally nothing he could do, as a young black man, that wouldn’t be viewed by police as suspicious.

Reflecting on the situation months later, the man told me the experience left him feeling like there was literally nothing he could do, as a young black man, that wouldn’t be viewed by police as suspicious. He had long grown accustomed to being arbitrarily stopped and frisked while walking through his neighborhood. But he had never been so cynical as to believe that the mere act of calling the police for help could result in his incarceration.

His experience, bizarre as it was, was not as uncommon as many people think. While many of us would like to believe that the implicit biases and stereotypes that animate disparate stop and search rates would subside in the face of something like a car accident, we know that this is not always the case. Within weeks of the young man’s release from custody, Renisha McBride and Jonathan Ferrell would lose their lives to gun violence—shot down by the very people they asked for help in the moment they needed it the most.